In today’s common speech, particularly in English, the word ‘ghetto’ clearly indicates a social and economic condition of marginality and exclusion. Ghettos are the poor neighborhoods of American cities, where poor people and ethnic minorities live and where lawlessness and violence prevail. In Europe, the word ‘ghetto’ is used to designate, for instance, the marginalized world of the Paris banlieue, and the word evokes the unspeakable horrors of Nazi ghettos in Eastern Europe. These events seem distant from Italy and from the Catholic Church, yet this centuries-old story began precisely in Italy.

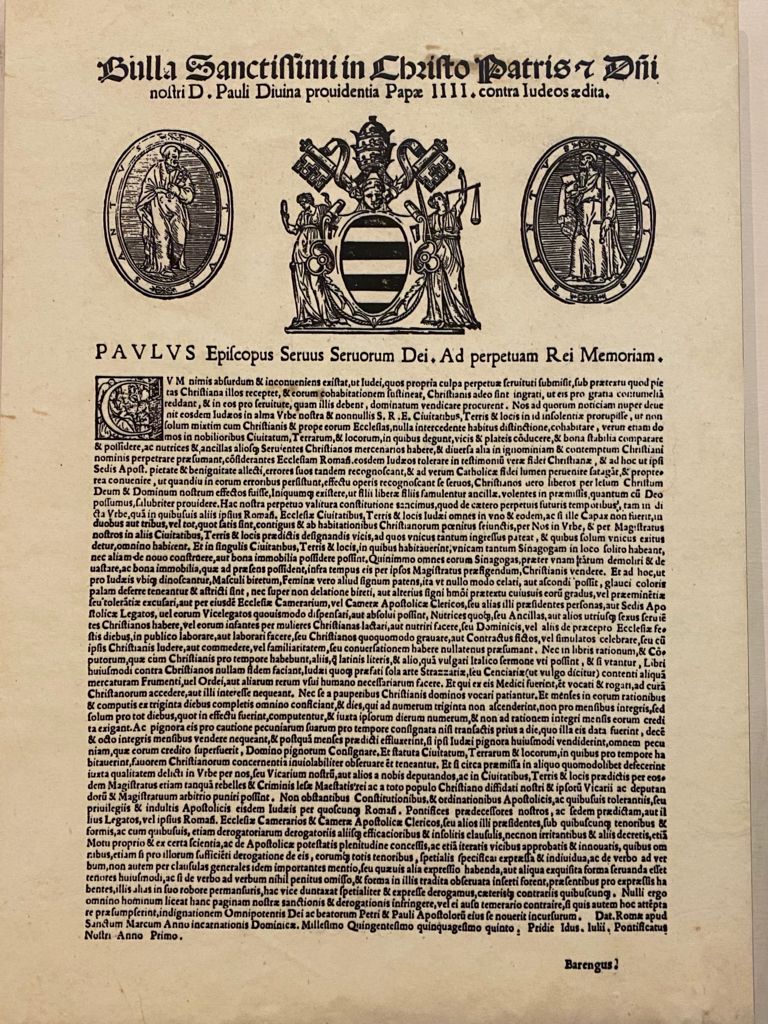

On July 14, 1555, Pope Paul IV, who had been elected less than two months before on May 23, promulgated the bull Cum nimis absurdum. From then on, until the country’s unification in 1871, that document radically changed the life of Jewish inhabitants of PAPAL STATES—and of one half of Italy. As is known to many, that was by no means an invention on the part of Pope Carafa: he merely copied a system of urban segregation that had been in force in Venice for 40 years, had already been successfully replicated in Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, Croatia) in 1546, and was expected to perform its task in Rome and in all Papal territories as well.

It would seem easy to explain what that task was and what results were achieved; yet this is not the case. The document aimed at regulating the presence of the Jewish minority within the Christian majority, but the ultimate goal and its actual consequences change according to the perspective from which one starts. If the chief purpose was to facilitate the conversions of Jews, then there is no question that it failed in the long run, notwithstanding the huge efforts made: though ghettoes existed for centuries and in spite of at least 2,000 baptisms, plus all the misfortunes, the discrimination and the humiliation, there are still Jews in Rome, and they are the direct descendants of those who chose to remain Jewish throughout the centuries.

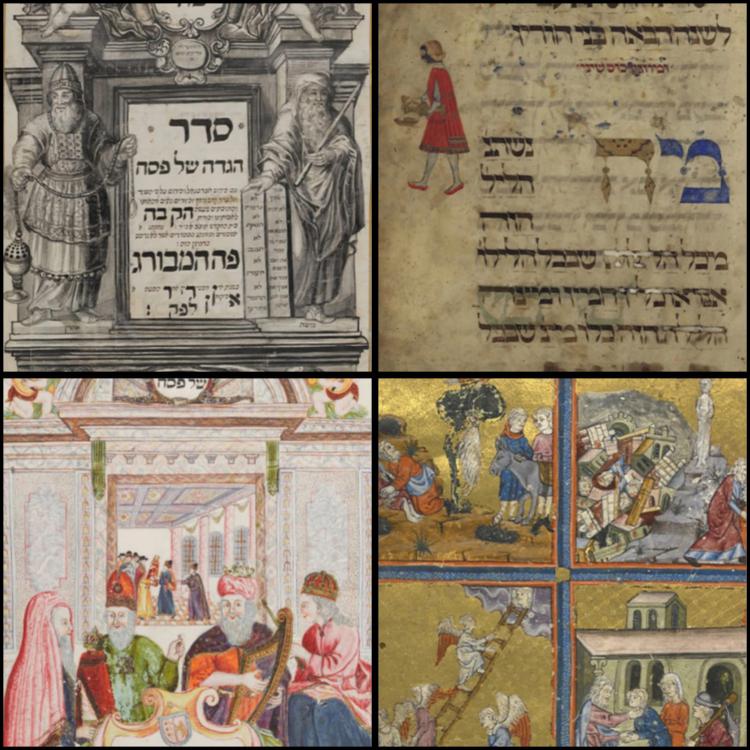

(1555 Papal bull establishing the Rome Ghetto – Courtesy Historical Archives, Jewish Community, Rome)

In the past few years, an exceptional wealth of international studies have rewritten the history of the ghettos. Thanks to new research, new sources and recent archival surveys, we now recognize the determination of those minority communities to preserve their identities in a hostile context. Countless studies have shown how the walls that separated Jews from Christians for centuries never really severed their relations, which remained fruitful throughout that long period of time thanks to the many exchanges—commercial and other—and in spite of occasional confrontations. The daily life of Italian ghettoes was always characterized by interaction, interconnection and exchange; this was possible because everyone knew the rules of the game. Paradoxical as it may appear, the discrimination imposed on Jews from the outside, and exerted by way of a range of limitations, established boundaries and behaviors that somehow still made contact possible between the two population groups. It was always clear who was who, what rules had to be followed, and what made this imbalance of power and opportunities work. The Jews knew they were Jews and they renewed on a daily basis their acceptance of their choice to live in the ghetto whatever the consequences. Still the fact remains that these consequences were an imposition and could not be avoided if not by accepting conversion and baptism.

The well-known restrictions on liberal professions forced Jews to rethink their traditional business activities and deeply redefined the Jewish world’s social hierarchies. On the one hand, the countless bans, culminating in 1682 with the prohibition of Jewish loan banks, pushed them to diversify their investments and to invent new versions of ancient crafts. On the other hand, the pressure of proselytism, of censorship, of attempts at isolating the ghetto from Jewish cultural networks pushed Jews to find alternative—and still partly unknown—ways of circulating texts and ideas.

On the other hand, the use of the Hebrew language was at least partly preserved in the drafting of the internal documents now conserved in the Historical Archives of Rome’s Jewish Community. Also, Rome’s Jews remained unwaveringly committed to providing Jewish education for young people and to supporting the poor. They incessantly protected and promoted their identity as a minority. Thanks to all of that, we now know the stories of those Roman Jews who chose to remain within the ghetto’s walls.

Today, the amazing exhibits of Rome’s Jewish Museum and others are the tangible expression of those stories. For example, donating silver objects or decorations to a Scola (Synagogue or Shul) was a vindication of the choice made for themselves and for their families present, past and future—a proof that they had weighed all options and proudly rejected other, perhaps easier but unacceptable choices.

Serena Di Nepi, PhD, is Associate Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Rome ‘La Sapienza.’ Among her publications, Surviving the Ghetto. Toward a Social History of the Jewish Community in 16th century (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2021; original edition, Rome: Viella, 2013)

(Translation by Marina Astrologo)